Using AI to Detect Anti-Competitive Legislation

I build a legal text classifier that correctly identifies up to 98% of paragraphs with potentially problematic provisions.

Competition is at the heart of consumer welfare. This is why in many countries, competition bodies assess new and existing policies for anti-competitive provisions. Competition Impact Assessment (CIA) studies are necessary for ensuring that regulations strike a balance between meeting sector-specific objectives and preserving a competitive market environment.

Ideally, most laws should be subjected to CIA and other types of regulatory assessments. But this is a time-consuming exercise: an initial review alone can take 2-4 months, according to an OECD1 representative I spoke to. With hundreds of new laws and regulations proposed in any given country each year, the need for an efficient approach to competition impact assessment is great. Having myself worked in the Philippine Competition Commission for nearly 4 years, I have first-hand experience of how such undertakings can severely strain resources.

Recent years have shown that machine learning and AI, particularly large language models (LLM), can greatly aid in processing massive amounts of textual data. Legal texts are no exception, and this is precisely what I demonstrated in my master’s thesis. I developed a pre-screening tool that (1) identifies legislation containing potentially anti-competitive provisions, and (2) categorizes these provisions into different types of restrictions that need to be flagged to CIA proponents.

AI is no replacement for an expert’s thorough assessment, and when enacting policies with wide-ranging ramifications, human judgment must remain the final arbiter. But automation can be useful as a means of initial assessment, with only those having problematic provisions meriting further review. Workloads would be significantly reduced. The machine learning models I trained were able to correctly classify up to 98% of text with restrictive provisions and accurately assign up to 77% of provisions to their respective categories.

Data: a corpus of legal documents

For my models, I used a database of legislative documents in countries where a round of OECD CIA studies was conducted. In all, I gathered a corpus of 273 texts from 7 countries. Each unstructured PDF was parsed to extract paragraphs containing relevant textual information, resulting in a total of 7,335 unique paragraphs of which 2,104 have been manually labeled based on the 4 categories identified in the CIA checklist of the OECD:

| Category | Sub-categories | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Limits the number or range of suppliers | Exclusivity rights, licenses and permits, cost of entry, geographical barriers |

| B | Limits the ability of suppliers to compete | Price regulation, advertising restrictions, unduly strict quality standards, cost of production |

| C | Reduces the incentive of suppliers to compete | Self- or co-regulatory regimes, publishing of sensitive business information, exemption from antitrust laws |

| D | Limits the choices and information available to customers | Buyer-seller information asymmetry, consumer switching costs |

Category D is lumped together with other miscellaneous provisions into a new category called Others. If a paragraph does not relate to any of the 4 categories, it is assigned a label of None. A good amount of processing had to be conducted to prepare the data for modeling. I discuss the data preparation step and provide an sample of the labeled dataset in this post.

Binary classification: is the law potentially anti-competitive?

Automating the initial screening of documents for CIA can be divided into two parts. The first task is identifying whether a law has provisions with potential anti-competitive effects. This is a yes or no question that I framed as a binary classification problem. To get the outcome variable, all four categories were encoded as with restrictions and none as no restrictions.

From here, I created a text classification pipeline starting with extracting features from the text. In NLP, feature extraction involves representing raw text as numerical values that can be understood and processed by machines. There are two main approaches to this: count-based and distributed representations. Count-based features rely on the frequency of word appearance in a document or corpus, while distributed representations or word embeddings are n-dimensional vectors that capture the semantic and syntactic characteristics of words. I used unigrams and n-grams for count-based representations2, and GloVe and Legal Word2Vec for word embeddings3.

I used these input features to train and validate machine learning models under different specifications, with logistic regression as benchmark and support vector machine (SVM) as the main model. Logistic regression is a widely popular technique for classification tasks because it is easy to implement and interpret. The model assumes a linear relationship among features and calculates the probability of an observation belonging to a certain category based on the appearance of these features. SVMs are more versatile and are capable of understanding non-linear relationships in data.

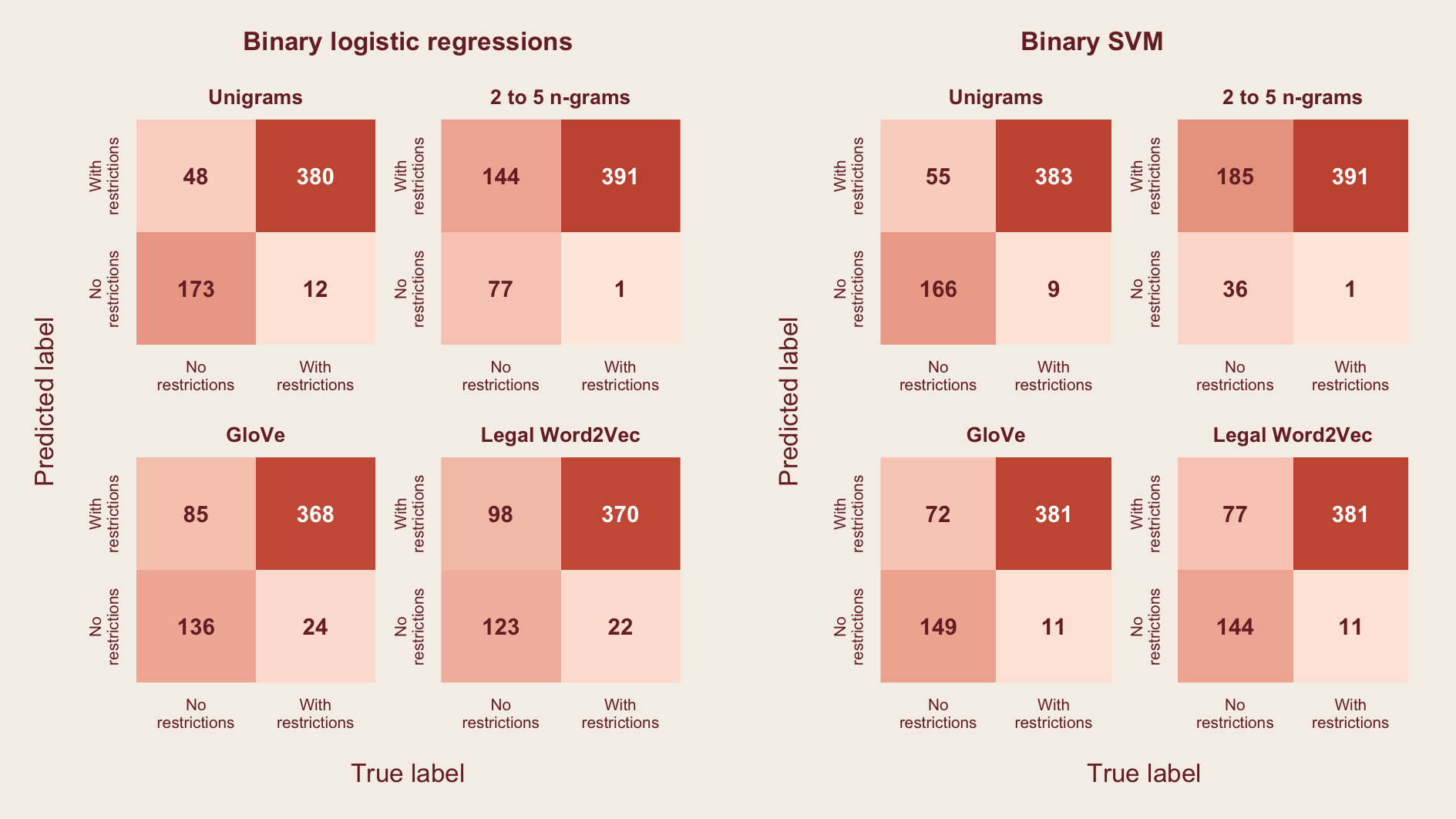

The figure below shows the results from the binary classifiers. Model predictions are represented as a confusion matrix. The upper right quadrant shows the number of paragraphs with restrictions correctly classified by the model (true positives), while the lower left quadrant shows the number of paragraphs without restrictions correctly classified by the model (true negatives).

Aside from maximizing these two metrics, it is also important to minimize to the lower right quadrant which shows false negatives. A high number of false negatives means that laws will be inaccurately tagged as not problematic when they in fact contain provisions that could restrict competition. For this particular use case, documents that are classified as no restrictions will not be further reviewed by experts. If paragraphs with restrictions are inaccurately classified, potential anti-competitive issues within the legislation are missed and cannot be properly addressed.

The best binary classifiers4 correctly can identify 94 to 98%5 of paragraphs with potentially anti-competitive provisions.

Multi-class classification: what kind of anti-competitive provisions?

The second part of the screening process involves categorizing paragraphs based on the type of restrictions present in the text – essentially a multi-class classification task6. This function is beneficial to practitioners in cases where specific types of anti-competitive provisions need to be prioritized.

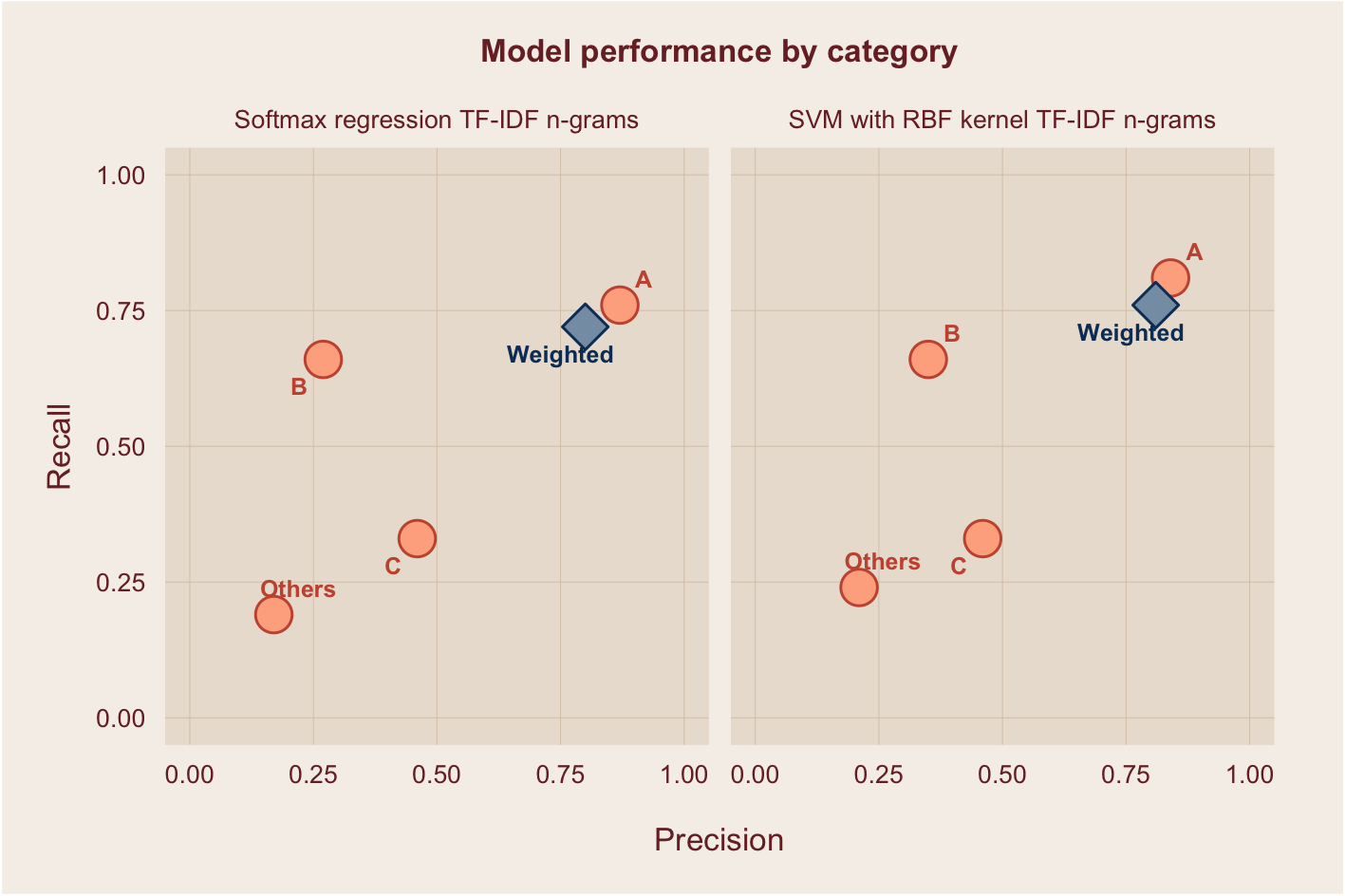

The same input features (unigrams, n-grams, GloVe, Legal Word2Vec) were applied to the multi-class equivalent of the logistic and SVM models7. The results were evaluated using precision8 (the proportion of true positives out of all predicted positives) and recall9 (the proportion of true positives out of all actual positives). As with the binary classifiers, it is important to minimize false negatives. This is demonstrated in high recall scores.

The figure below shows the performance of the best classifiers. Overall, the models were able to correctly categorize the type of restrictions in up to 77% of texts. However, it is noticeable that the performance varies across categories. Classifiers were able to accurately identify up to 80% of paragraphs belonging to category A, and up to 68% of paragraphs belonging to category B. The subpar performance for categories C and Others can be attributed to data imbalance, which I discuss in more detail in the data post. Overall, the performance of the multi-class models are comparable with similar legal text classification studies10.

Semantic similarity approach: when labels are not available

The performance of classification models can be improved by collecting more labeled observations. In many cases, the most precise way of gathering data is through manual annotation of documents. However, this approach is not always practical and feasible.

As an alternative, I conducted an experiment that explores semantic textual similarity (STS). This is an unsupervised learning approach that minimizes reliance on labeled data. STS involves comparing the representations or embeddings of two pieces of text using a distance measure or a similarity score. The higher the score, the more likely it is that a text pair is related.

To implement this, I created verbalized labels. Instead of using a categorical variable as in typical classification tasks, key words and phrases were assigned to each label. The verbalized labels were taken from the OECD’s description of the four potential restrictions in their CIA toolkit. All paragraphs were paired to each of the verbalized labels, and similarity scores were calculated. An arbitrary threshold was set to determine whether the text can be classified into a particular label.

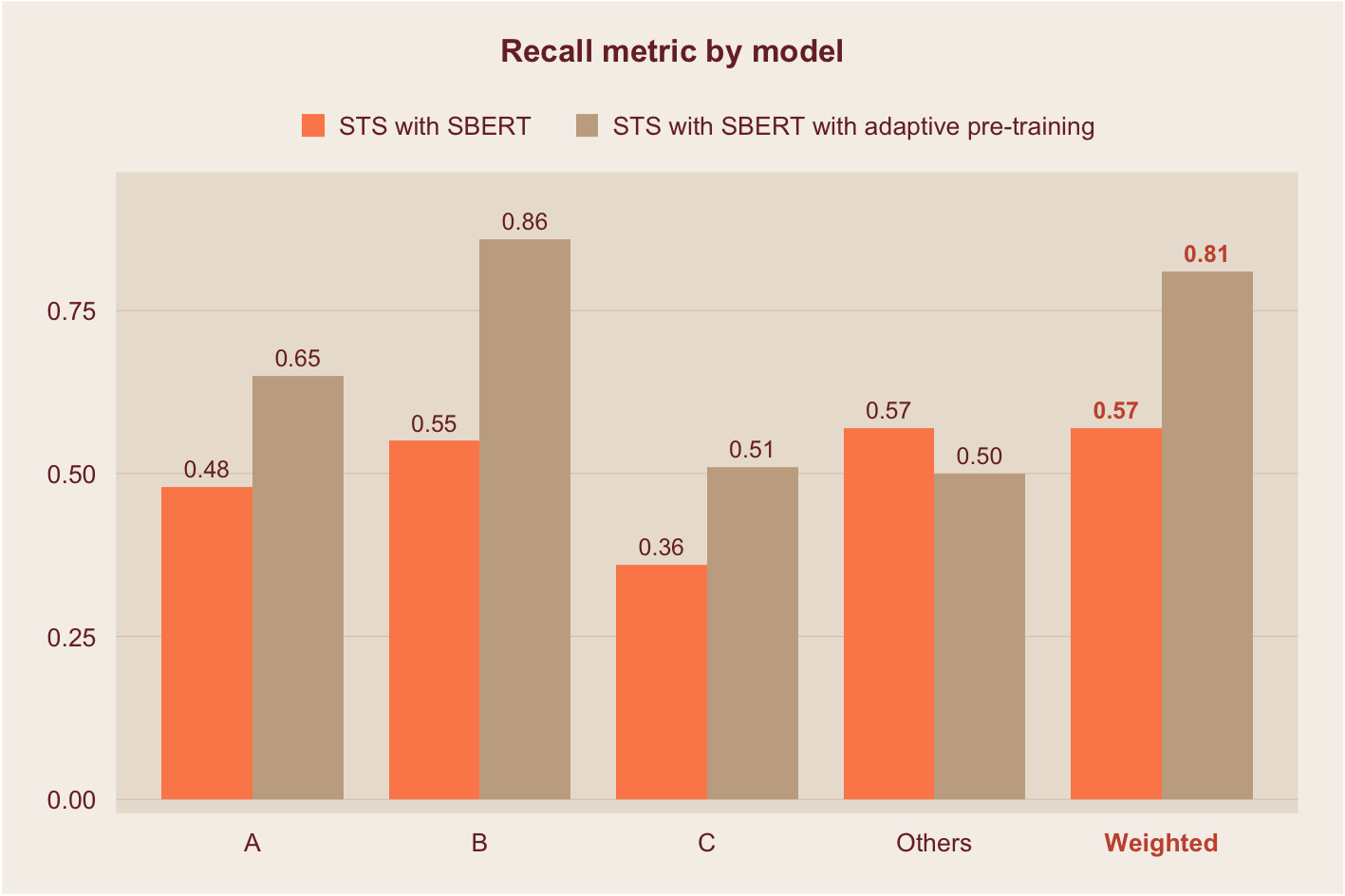

The embeddings used to calculate similarity scores were derived from variants of the widely popular Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers or BERT. The first model applied pre-trained Sentence BERT (SBERT) embeddings. In the second model, the embeddings were improved using a technique called domain adaptive pre-training. This step introduces additional information specific to the legal text corpus, as opposed to relying on the more generic embeddings from base BERT.

The figure below shows the results of this threshold-based classification using STS. As expected, the model with domain adaptive pre-training was able to correctly classify more paragraphs with restrictions. The model has a weighted average recall of 81% across all categories – it is able to correctly classify the type of restrictions in up to 81% of texts. It also outperforms the previous models in the underrepresented categories, C and Others.

The results of this study demonstrate how AI can benefit the legal profession. The applications of a text classifier extend beyond competition regulation. The same principle can be used to detect provisions relating to any number of policy outcomes, from climate to migration. Through the creative application of machine and deep learning models, the time spent on repetitive tasks can be greatly reduced, allowing human minds to focus on deeper analytical work.

More details about this project can be found in this repository.

Footnotes

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development↩︎

In particular, a TF-IDF (term frequency inverse document frequency) matrix. Unigrams are single words, while n-grams are phrases that are 2 to 5 words in length.↩︎

GloVe embeddings can be downloaded here and Legal Word2Vec can be downloaded here.↩︎

More than 4,200 binary model specifications were trained and tested using different hyperparameter combinations. The best models were selected through a grid search algorithm.↩︎

Given by the formula \(TP / (TP + FN)\)↩︎

In multi-class problems, labels are mutually exclusive so only one label is assigned per text. In reality, there could be more than one label per document (a multi-label problem). But for demonstration purposes, I choose to the simpler multi-class specification.↩︎

Softmax and multi-class support vector machines↩︎

\(TP / (TP + FP)\)↩︎

\(TP / (TP + FN)\)↩︎

Such as Shaheen, Wohlgenannt, and Filtz (2020) and Gao, et. al. (2020).↩︎